Artists have long been influenced by their predecessors. While this often means a nod to artists they admire by incorporating their imagery into their own work, at other times its is an act of rebellion against artistic expressions deemed antiquated or controversial for any number of reasons.

Norman Rockwell, known for his illustrations of 20th century America, was a classically trained artist who resigned from his position at the Saturday Evening Post to join Look Magazine so he could share his views on issues such as Civil Rights and wealth inequality. Think his “A Problem we all live with” which shows Ruby Bridges entering an all-white school under the protection of federal marshals, a topic deemed too risky by Post Editors.

His Rosie the Riveter illustrates his influence of Michelangelo’s Prophet Isaiah from the Sistine Chapel. It is easy to see how closely Rockwell studied this iconic image as a way of elevating his own status as a classical artist.

Norman Rockwell was classically trained and often referenced historical works of art in his magazine covers.

Michelangelo’s Prophet Isaiah is one of the most recognizable images on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

He portrays Isaiah as a prematurely graying man of great beauty whose body is young and vigorous-full of energy and movement. Both elegant and powerful-just look at those biceps! Isaiah is the image of the poet-sophisticated and romantic, he holds a book, the format of his craft, as an angel draws his attention toward the image of Christ’s birth on the high altar. This is an appropriate interpretation of Isaiah’s poetry session as he is known for his prosaic predictions of the virgin birth. We look at both figures from below, making them loom larger than real life.

Norman Rockwell’s model for Rosie the Riveter was 19-year-old telephone operator named Mary Doyle. The painting, which appeared on the front cover of the Saturday Evening Post in May 1943, quickly became a symbol of the millions of women doing war work while their men were at the front.

Doyle was paid $10, roughly $140 in today’s values for two days of posing for Rockwell’s photographer. The painter later apologized for bulking up her relatively petite figure to give the picture more impact.

Doyle was the daughter of a Vermont logger who went on to graduate as a dental hygienist. The original painting sold in 2002 for $5 million dollars.

Muscular and tough, she eats a ham sandwich brought from home. The riveter rests in her lap. Riveters were used to construct fighter planes.

Her lunchbox with her name on it sits behind the riveter. She is on a mission, even on her lunch break, she is alert and on duty. She wears loafers with bright red wool socks. Her foot stomps on a copy of Hitler’s Mein Kamph.

A cosmetic compact and handkerchief are sticking out of her pocket. Judging from her very red lips, she has just applied her lipstick. A Red Cross pin and a Victory pin show her patriotism and act as a necklace.

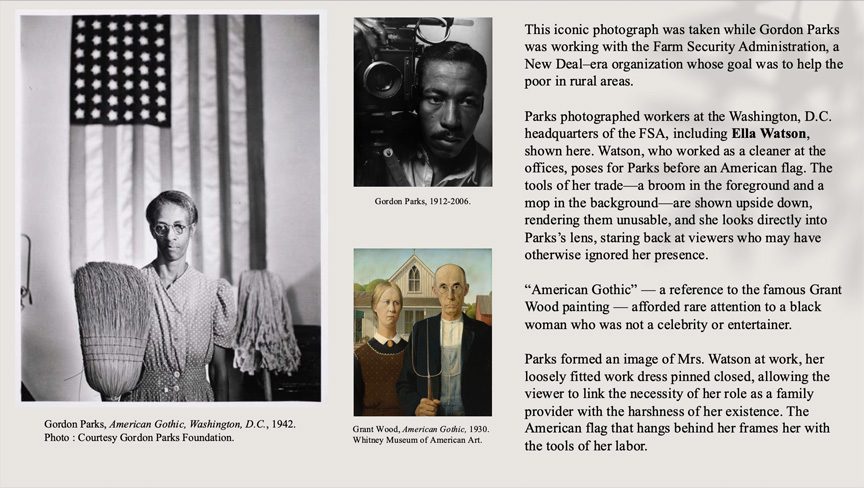

This iconic photograph was taken while Gordon Parks was working with the Farm Security Administration, a New Deal–era organization whose goal was to help the poor in rural areas.

Parks photographed workers at the Washington, D.C. headquarters of the FSA, includingElla Watson, shown here. Watson, who worked as a cleaner at the offices, poses for Parks before an American flag. The tools of her trade—a broom in the foreground and a mop in the background—are shown upside down, rendering them unusable, and she looks directly into Parks’s lens, staring back at viewers who may have otherwise ignored her presence.

“American Gothic” — a reference to the famous Grant Wood painting — afforded rare attention to a black woman who was not a celebrity or entertainer.

Parks photographed an image of Mrs. Watson at work, her loosely fitted work dress pinned closed, allowing the viewer to link the necessity of her role as a family provider with the harshness of her existence. The American flag that hangs behind her frames her with the tools of her labor.

(Left) Jaune Quick–to–See Smith, The Red Mean: Self-Portrait (1992), collection of the Smith College Museum of Art. (Right)

he Red Mean: Self Portrait by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

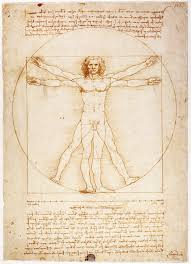

Pasted across the chest of a human figure outlined at the center is a bumper sticker that reads “Made in the U.S.A.” The background is a collage of Native American tribal newspapers, inviting viewers to do some reading. Thus even if the central figure itself quotes Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, the message here is autobiographical. Leonardo inscribed his human form within a geometric framework to emphasize its perfection, while Smith places her silhouette under the red X that signifies radiation. She alludes both to the uranium mines found on some Indian reservations and also to the lamentable fact that many have become temporary repositories for nuclear waste